On Such Things That Vanish

notes from a downtown garage

This past weekend, I was quite sure I’d lost my car.

In my mind, it was less likely that an unknown agent had thrown a rock through the window and hot-wired the car out of the garage, but rather that the car itself had simply disappeared—mysteriously, like Lina’s daughter in Ferrante’s Neapolitan novels. It happened in the evening, as I tried to make my way home from the poetry reading of my long term acquaintance (and National Book Award finalist!) Gbenga Adesina.

I have always struggled with spatial disorientation; years of driving in Lagos and Virginia with no sense of where I am heading. I have no way to compute what 600 ft is, much less where to turn right. When I return to familiar spaces, I tend to remember a leaf, the shape of a tree, but not a landmark. Not even to save my life. This means that I am almost always getting lost. Sometimes it takes me a long while to recall where I parked. It is a common predicament, true, except you can scale mine by a hundred. But I have also developed a system that works: I venture to events about thirty minutes early to account for “getting-lost” time. I also internally re-map my parking location by charting things like exits, smells, the color of the car next to me etc. Finally, to lock everything in place, I take an actual live picture of the parking lot and row number. No time for delays.

Anyway, Saturday. Evening had fully settled over downtown, so the lights from the buildings spilled into the streets and created an atmospheric promise, regardless of whether you were heading home or just starting the night.

I was heading home.

I got to the garage, to the designated Row where I parked, but my car was missing. What? I walked around, to the right and left. I even saw the car that was parked next to me. I’m sure of it. Yet my car was still missing. Then, I walked to the fourth floor, walked all the way down to the first floor. Retrace your steps, I thought. So I did. I combed the whole mighty garage on foot. Twice. No car.

I was exhausted but I had also met my step count for the day. I started to ask strangers fumbling with their car keys where to report a car theft—since I could not say a car had vanished. I almost cried. Then I cried. Over an hour had passed at the time and my car was still missing. I was almost at the point of resignation, deciding to call an Uber to take me home, that I had an image that came to me from inside, like the beginning of my stories—or my novel, This Kind of Trouble. It was this image/knowing that came, and then I understood that I was, in fact, in the wrong garage.

Ah.

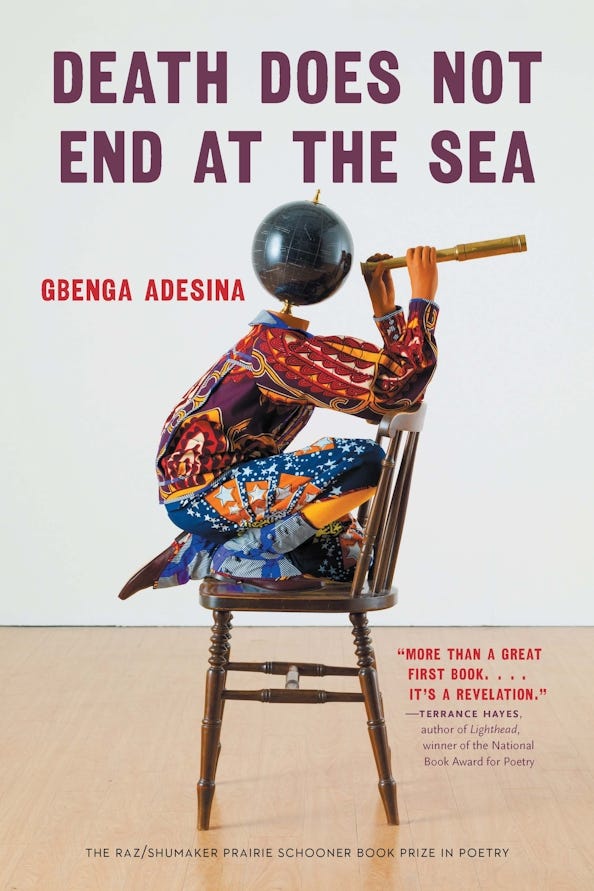

And sigh. Okay, I really wanted to get this pitiful experience out of my system. But I also wanted to talk about something similar that Adesina said while reading from his new collection, Death Does Not End At The Sea at New Dominion Bookshop—something about stripping down to the “precision of the image.”

Adesina is one of the more solid poets I know—a giant thinker and feeler. I loved his approach to engaging his listeners, and reading for each one a poem that might match the context of their life. In one of my favorite passages, an elegy for his father, Adesina invokes the domestic and the sacred as petition and command, as though a unit as small as a blank page is large enough to hold an eternity of questions and prompts. Here he writes:

“My mother put her mouth to my father’s ear,

Christ to Lazarus, and said, “Wake up. I command you.

Wake up.

You belong to me.

Your body, clove, rosemary, bread,

it belongs

to me. Rise, on this third day.

I know your name. Wake up

Please, do not fail me.”

The “Please” addressed to a transcended lover is as wrenching as the futile declaration “you belong to me.” It is here, in this image of mourning, that many of the poems converge for me.

I asked Adesina his approach to making language say the things he wants it to say. How does poetry do so much with so little? His response (paraphrased) is to keep fidelity to the precision and preeminence of the image. He explained from the position of a poet’s craft, that we come to language with prejudice and bias, and it is the poet’s job to write from the end of his own meanings—after they have reached the end of their vocabulary, syntax, rhetorical context, politics, even affections. (Again, I paraphrase).

When, for example, the descriptors of a nose or a face or an ear have been exhausted; this is the place that the poem has to work its way up from. It is the specificity of nothing, or the specificity of the non-verbal, the non-discursive—or like I prefer these days, the substance of things. What is the substance of grief, I wonder? No one poem can tell us that; here we must rely on the chorus of life itself, in our kinship with all the things we, too, have lost, we soldier on with our own distinct images, our scars like maps.

Perhaps this is what his collection is about—seeking that thing. Maybe this is where all poems come from; not knowing, but seeking. That is to say that poetry seeks what language, what prose has left behind. And we all, seek alongside all other seekers.

The other day, I sat with GPT in an anxiety-induced rant to discuss the language models of AI; The way that A.I’s words are derivative of data and patterns, but have no inner life, no subjectivity or personal hunger; no soul in which to carry grief, or to pin its image. We, myself included, insist on the thoughtless words of GPT to produce thought in us, because our “meanings” we insist, can be formulaic; a life of symbols and gestures, structure and form—but no light. Worse, a life shaped after the substance of past things. Stolen things. Repurposed things. A present-now animated by ghosts past.

Language is at risk, we tend to agree. But so is inner life. We will be the most efficient we have ever been. But it comes at a price. I want to believe that on this, at least, the image is clear.

Mapping the smell of a place is so impressive.